Peoples indigenous to that land have since been forced to battle an equally brutal government for the right to simply exist. Centuries of exploitation and genocide have corralled these original inhabitants into (in many cases) arbitrary areas politely termed “reservations” — but are decidedly more akin to 1930’s German ghettos.

And the government of these so-called ‘United’ States still continues its exploitation, as in its surreptitious alignment with Big Oil to allow construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline which will likely contaminate the Standing Rock Sioux’ drinking water — and that of some 18 million people, all told.

Thanks for nothing, Columbus.

But in light of the stark reality of the conqueror’s brutal legacy, a few shining moments of resistance evidence the power of the indigenous to quash governmental usurpation — as is the innate right of humans anywhere.

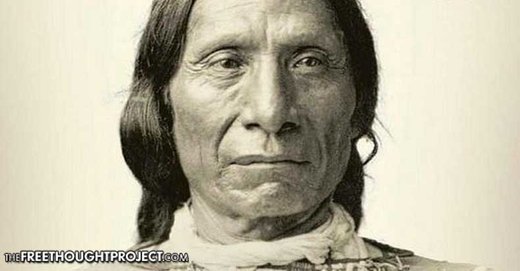

Considered most successful of these rebellions is the war led by Red Cloud — the English name of the warrior, statesman, and Oglala Lakota Sioux chief Mahpiua-Luta — against the U.S. military beginning in 1866.

With the discovery of gold in northern Wyoming and southern Montana in the early 1860’s came the need for a route for miners and European settlers advancing west and north — but the simplest route traversed the Powder River country already set aside by the government as hunting territory for the Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and several of the seven bands of Lakota.

John Bozeman, despite warnings against incursions into Native American lands, blazed a trail along a path long used by indigenous peoples through the Powder River Basin — a less arduous route than one to the west that didn’t trespass into designated Native lands.

This path came to be named the Bozeman Trail — and the government’s quest to protect the European invaders who wished to travel it led to a bloody and decisive victory by Red Cloud and his allies.

After Col. John M. Chivington needlessly massacred an estimated 150 Arapaho and Cheyenne men, women, and children in 1864 in Colorado Territory at a peaceful camp on Sand Creek, survivors fled north to the same Powder River country, attacking white settlers along their way.

WyoHistory.org writes:

“Early in 1865, bands of the Cheyenne, Oglala Lakota and Arapaho tribes set up huge camps on the Tongue and Powder rivers in northern Wyoming. That summer, thousands of warriors moved south and on July 26, 1865 attacked Platte Bridge Station, an army post where the emigrant road crossed the North Platte, and killed 26 men. Among them were Lt. Caspar W. Collins, for whom the city of Casper, Wyo., is named.”

To protect the settlers and miners traversing the Bozeman Trail to Montana Territory gold mines, the U.S. military initiated the euphemistically-titled 1865 Powder River Expedition headed by District of the Plains Commander Brig. Gen. Patrick Connor as a brute force method of quelling the tribes.

“A second column, led by Col. Samuel Walker, made its way east of the Powder River toward Montana, and the third, led by Col. Nelson Cole, crossed Nebraska Territory and met up with Walker north of the Black Hills. Walker’s and Cole’s men suffered from terrible weather, dying animals, confusion in the badlands and demoralization, and limped into Fort Connor as ‘the sorriest army ever seen in Wyoming,’ according to historian T. A. Larson,” WyoHistory.org continues.

Those three columns consisted of around 2,675 men whom the government forced to wear outdated and insufficient uniforms leftover from the Civil War. This bedraggled bunch came under attack and generally failed to accomplish any decisive victories against their Arapaho and Lakota rivals, although its efforts succeeded in solidifying Native resistance.

By autumn 1865, the U.S. government attempted several treaties with Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota leaders — but many, including Red Cloud, refused to negotiate, much less sign, any monetary agreements to allow settlers safe passage through the Bozeman Trail and Powder River Basin.

Amid ongoing treaty negotiations, the U.S. War Department deployed 700 troops and hundreds of their family members and civilian contractors headed by Col. Henry B. Carrington to the river basin in 1866 — though they were poorly equipped to handle the terrain, weather, and the highly skilled opposition.

Carrington founded Fort Phil Kearney on the Little Piney Creek and then moved on to do the same further north,leaving behind enough men to finish construction.

“In December, a band of Oglala and Minniconjou Lakota warriors led by Red Cloud, Crazy Horse and High-Back-Bone lured Captain W. J. Fetterman over a rise near Fort Phil Kearny and into a trap. Within half an hour, Fetterman and all 80 of his men were dead.”

Fort Phil Kearney and areas nearby came under successful attack by Red Cloud and his warriors in subsequent months. Eventually, the military provided faster-firing ‘breech-loading’ rifles for the fort’s troops, who then managed to better stave off attacks from the Native warriors.

But the government, more concerned with protecting construction of the transcontinental railroad, realized keeping troops positioned to guard the Bozeman Trail would deflect too much manpower — and once again summoned Red Cloud to the negotiating table at Fort Laramie in 1868.

Red Cloud again refused to meet with the so-called peace commissioners until the military abandoned Fort Phil Kearney and two others in the Powder River Basin. Left without viable options and the need to move troops elsewhere, the Army evacuated and regrouped at Fort Laramie — leaving Red Cloud, the Lakota Sioux, the Cheyenne, and Arapaho the clear victors in the war.

As the Army withdrew from the forts, the warriors quickly burned them to the ground.

In November, Red Cloud finally arrived and signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which created the Great Sioux Reservation, encompassing all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River and included the Black Hills — the exact area in which the Standing Rock Sioux are now forced to resist in order to protect their drinking water from Big Oil.